A Cyclist’s Guide to Functional Threshold Power

Functional Threshold Power (FTP) has long been held as the gold standard when it comes to quantifying performance in competitive endurance athletes. With the cost of a power meter now well within reach for most cyclists, riders of all abilities now have the means to objectively see how their performance is improving – or deteriorating, over time. But is this measurement even important in what you personally do as a cyclist, and if so, how do you go about improving that number?

Functional Threshold Power (FTP) has long been held as the gold standard when it comes to quantifying performance in competitive endurance athletes. With the cost of a power meter now well within reach for most cyclists, riders of all abilities now have the means to objectively see how their performance is improving – or deteriorating, over time. But is this measurement even important in what you personally do as a cyclist, and if so, how do you go about improving that number? In this article we’ll take a deep dive into all things FTP – what it represents, how to measure it, and how to improve it.

What is FTP?

Let’s start with the idea of a threshold. As exercise intensity rises, the increasing demand for energy means that the muscles’ aerobic energy production systems are supplemented and eventually taken over by a process called ‘glycolysis’ where carbohydrate in the form of glycogen is broken down, producing lactate which can supply the muscles with energy without combining with oxygen to do so. A byproduct of this reaction is the accumulation of hydrogen ions causing the blood to become more and more acidic to the point where further increases in intensity are unsustainable. A graph plotting blood lactate levels against some exercise intensity indicator – usually heart rate, shows an exponential increase in lactate where the body’s ability to clear out the byproducts of glycolysis is outpaced by the rate of accumulation. This point is referred to as the Lactate Threshold (more accurately ‘Lactate Threshold 2, LT2) or sometimes the Onset of Blood Lactate Accumulation (OBLA).

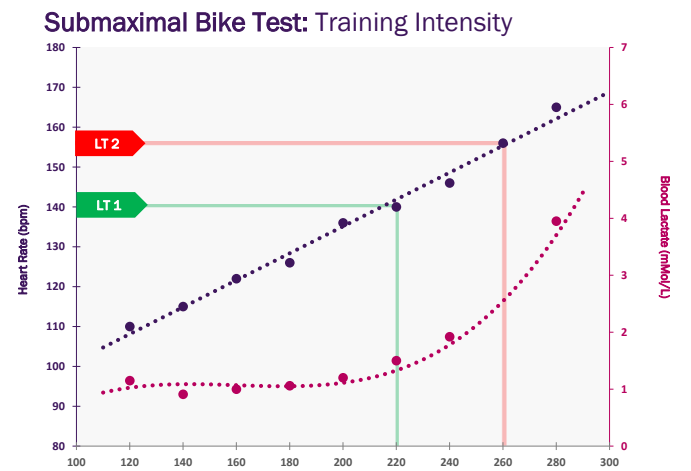

At LT2, blood lactate concentrations are rising rapidly corresponding to a threshold power of 260 Watts at a HR of about 156 bpm (red line on graph). LT1 is where blood lactate first begins to rise from baseline and marks the start of where glycolysis begins to supplement the aerobic energy system to replace ATP in the working muscles.

So the power you are able to produce at this threshold (LT2) would obviously be your ‘Threshold Power’. This is a level of power that you can just about sustain for a long period before rapidly increasing blood acidity means any further increase in power is unsustainable. The ‘Functional’ part of ‘Functional Threshold Power’ comes from making an estimation, out in the field, of where this threshold is based on functional testing outside of a lab environment. We estimate FTP basically by seeing what the maximum power an athlete can sustain is over a period of one hour.

How Accurate is FTP Testing?

Ideally we would just ride as hard as we could for one hour to get a true value of FTP. However, this kind of effort is something any sane cyclist would not want to do more than once, if at all. Therefore, various protocols have been developed to make testing easier including variations on a 20 minute effort test, as well as tests that ramp up resistance in incremental steps until the rider can no longer sustain the effort. Limitations in these protocols as well as variations in environmental factors mean that these tests can have varying degrees of accuracy. Indeed, it has been shown that most riders who have obtained a threshold power value functionally, can in actual fact only sustain that output for around 30-40 minutes rather than the full hour. Furthermore, there are measurable differences between the power that can be sustained when riding indoors on a stationary trainer and when outside on the open road or trail. This difference in power can be as much as 10-20% depending on individual setups as well as overall athlete level of fitness.

It should also be noted that the power threshold is not like an on/ off switch. It is not true to say that below threshold you can pedal indefinitely, and above that power level the lights suddenly go out. You are still dealing with a considerable amount of blood acidity. How long you can sustain that level of discomfort depends a lot on your mental fortitude and your willingness to suffer – working at 95% of FTP is still a hard place to be.

What’s a Good FTP, and How Much Improvement Can You Really Make?

Unless you ride and race exclusively on flat terrain, a high absolute FTP is relatively unimportant since gravity will take its toll on the heavier riders, and even those with a high absolute FTP value will struggle to keep pace with their lighter peers when the road tilts up. In this case Watts /Kilo is the more important metric. In a flat time trial however, those with more lean muscle mass and high absolute FTP will have the advantage, all else being equal. A good FTP then, is relative to a rider’s weight. Something like 4 W/Kg would be a good number to work with if you wanted to be competitive in an amateur cat 3 road race for example.

It is important to realize that there are genetic limitations to achieving a high power-to-weight ratio, and that just because someone you know of the same age has a particular FTP value, there are a couple of very good reasons why you may not ever be able to match that power in absolute terms. One reason is the ratio of ‘slow twitch’ (type 1) to ‘fast twitch’ (type 2) muscle fibers. All bodies are different and while it is possible to have some fiber type conversion with the right training, for the most part those born with a naturally high proportion of slower twitch muscles will have an advantage when it comes to sustained power output, while those with more type 2 fibers will have more high-end and explosive power. Type 2 fibers rely more on glycolytic energy production than the more aerobically efficient type 1 fibers, and hence tire more easily.

Additionally, there are body geometry factors that influence the ability to generate power sustainably. Contracting muscles cause movement around a hinge point or ‘fulcrum’, for example at the knee or the hip. Where your muscles attach to the bones in the leg matters, with those with bones attaching distally lower down the limb having a mechanical advantage – more movement for any given contractile force meaning less work over time, equaling less fatigue for a given amount of sustained power.

Does FTP matter?

Trying to stay motivated and keep on track toward your performance goals can be hard. Unless you are relatively new to endurance sports, progress can at times be hard to judge, and in this respect having an objective way to quantify your progress is invaluable. The gold standard for assessing an athlete’s level of fitness is by comparing how well you perform at threshold versus your performance at the intensity where your body is utilizing its absolute maximum amount of oxygen (VO2max). A high threshold heart rate as a percentage of maximum heart rate is an indication of a fit athlete. Note that this is a ratio, so no particular units are implied – in cyclists we look at power output at threshold versus power at VO2max. In runners or swimmers it is generally expressed as pace. As training progresses, it is hoped that we see an increase in this percentage value, so while many athletes have reached, or come close to their genetically limited ceiling as far as VO2max goes, there is most often room to push up threshold power /pace with the fittest among us achieving a ratio of 85-90% of VO2max.

As with all training, the more you do something, generally the better you get at it. So, training specifically at or around your threshold power will hopefully give you a better threshold power. This is very important if you are a triathlete, marathon runner, or most of your bike racing is doing longer time trials. However ,in an average mass-start road, gravel, or mountain bike race, the ability to put out a hard sustained effort for an hour plus, doesn’t always get the job done. Unless the course involves longer climbing sections, or you find yourself in a solo breakaway, other performance metrics often carry more weight. Leaving aside your ability to execute a tactically smart race, being able to hang on to very hard but short surges in pace or put down a strong sprint after many miles at zone 2 or tempo pace, is often much more important than having a high FTP.

Bike racing is very different to running marathons or competing in a triathlon. The intensity demanded can vary rapidly from one mile to the next, and so consequently you need to hone all of your energy producing systems, not just threshold power. The good news is that if you have approached training for a high threshold power in a methodical, structured manner, you have most likely made big improvements to your 5 minute power and even your 5 second power.

How to Raise FTP Through Training

To achieve adaptations to a specific body energy system, training specificity and progressive overload are the key concepts. At threshold power intensities, the body is still using a combination of oxidative and glycolytic processes to replenish ATP in the working muscles, and training right at or close to your current threshold power will elicit efficiency improvements in both of these systems. As improvements are made, the intensity needs to increase, applying just the right amount of stress so that the body continues to adapt.

At threshold, the buildup of lactate and associated byproducts in the working muscles is increasing at a rapid rate, and while it is possible to build up a tolerance, both physically and psychologically to this increasing blood acidity, a better approach is to improve the body’s ability to flush, or ‘shuttle’ these metabolites from the working muscle fibers. So-called ‘lactate shuttle’ intervals work by spiking muscle lactate concentrations with brief bursts of power above threshold before settling straight into periods at just below threshold where the work of removing the acidity takes place. As lactate shuttling efficiency improves, we progressively overload the system with incrementally more challenging intervals, pushing up threshold power further.

Lactate shuttle intervals work by first spiking lactate levels with short bursts of power above threshold, and then attempting to clear the lactate and associated byproducts during a longer effort at sub-threshold power.

While lactate shuttle style intervals have been proven to be highly effective, two additional approaches to FTP improvement are worth mentioning here. Firstly, by improving aerobic fitness with plenty of zone 2 riding, we can effectively shift the lactate level /workout intensity curve on the graph to the right. Having a highly trained aerobic system means that the contribution of glycolysis to energy production happens at a higher intensity and therefore the onset of blood lactate accumulation (OBLA) is delayed. Secondly, there are instances where athletes have a high FTP relative to their VO2max but with a low absolute FTP value. In these cases it can be that there is plenty of room for improvement in maximum oxygen uptake, and training should focus on ‘pulling up’ FTP by doing more VO2max focused intervals.

In conclusion, while FTP might not be as important to you as a cyclist than to your marathon running, or time trialing brethren, it is an important metric for gauging your own fitness level. Test for FTP at the beginning of a training block and test again at the conclusion to get an objective indication of whether your training has been effective. Specifically improve your FTP by doing lots of work at or around your threshold power, and include a lot of ‘lactate shuttle’ type intervals. Training specificity and progressive overload are key to making improvements.

How to Become a Better Climber - Sprinter’s Edition

Skeletal muscles are composed of fibers with markedly different characteristics. Generally fibers are classified as either fast twitch or slow twitch. The ‘twitch’ being the time taken for a motor unit to develop force and then relax. A motor unit consists of the motor neuron (the electrical signaling pathway) and the fibers it innervates. Commonly identified fiber types are type 1 (slow twitch), and type 2A, or type 2X (both fast twitch). Type 1 fibers are smaller than type 2 fibers and appear red in color due to the high concentration of blood capillaries. With a higher amount of blood flowing in and greater mitochondrial density, these muscle fibers are efficient, fatigue resistant, and have a high capacity for aerobic energy supply. However type 1 fibers have limited potential for rapid force development. Type 2 fibers, by contrast, can produce rapid force development but become fatigued quickly. Type 2 fibers are generally larger and respond well to high intensity loads such as weight training.

Baker City Cycling Classic. On the Ropes and Off the Back

Last year was my third bash at the Baker City Cycling Classic (BCCC), a three day stage race in Eastern Oregon. The defining moment came for me in the last ‘Queen stage’ on the second of three sustained climbs we needed to negotiate before a long run through a valley and the last long uphill ramp to the finish after 100 miles of racing. This is where my race was essentially over. I dug myself into a hole trying to stay with the group and then, with all matches burned, I lost sight of them as we went over the top. At that moment I could still, annoyingly, hear other riders talking somewhat casually, as I was fighting for breath. What just happened? Really? Was I really that much less ‘fit’ than my adversaries?

Back at the hotel that evening I was talking with my teammate, Chris, who remarked that he too was getting over those passes “right at FTP”. Now Chris is the most modest, least ego-driven guy I know, so I knew that his 300W FTP was where he was at over the top of those climbs. “Dude! FTP? I was beyond VO2max! Crazy. Now undoubtedly Chris is a little younger and far more gifted than me as an athlete. But the disparity in our perceived exertions on the same stretch of road was striking. For BCCC I had been training for months, and had lost over ten pounds in weight. I was convinced that my now lean 160 pound frame would get over those passes just as well as anyone else in that group. Evidently it was not to be.

This has all got me thinking about body types and whether we’re all eventually destined to just do well in what we do well in. I can sprint. Chris can’t sprint. I’ll see 1200W on a determined push for the line. Not too shabby for a guy in his sixties. But is that all I can do? Am I a one-trick cycling pony? When I look in the mirror, I see muscle. Not body builder muscle, but you know – defined I guess. A ‘mesomorph’. Thinking about the guys I was up against that day, there were a lot of ‘ectomorphs’ – long lanky limbs, narrow hips, skinny dudes. Something is playing a big role in their climbing performance other than the fact that they obviously were lean. The clue was in the ‘shape’ of those bodies, not just the weight of them. That something turns out to be the type of fiber making up their locomotor muscles.

It’s probably safe to assume that guys like Robert Forstermann have a large proportion of fast-twitch fibers in their muscles.

Muscle Fiber Types and Realizing Your Potential - or Lack Thereof

Skeletal muscles are composed of fibers with markedly different characteristics. Generally fibers are classified as either fast twitch or slow twitch. The ‘twitch’ being the time taken for a motor unit to develop force and then relax. A motor unit consists of the motor neuron (the electrical signaling pathway) and the fibers it innervates. Commonly identified fiber types are type 1 (slow twitch), and type 2A, or type 2X (both fast twitch). Type 1 fibers are smaller than type 2 fibers and appear red in color due to the high concentration of blood capillaries. With a higher amount of blood flowing in and greater mitochondrial density, these muscle fibers are efficient, fatigue resistant, and have a high capacity for aerobic energy supply. However type 1 fibers have limited potential for rapid force development. Type 2 fibers, by contrast, can produce rapid force development but become fatigued quickly. Type 2 fibers are generally larger and respond well to high intensity loads such as weight training.

Your muscles’ motor units are recruited in a sequential order depending on the force demanded of them. This is known as the ‘size principle’ where smaller, low force-producing type 1 muscle fibers are recruited first, having a low recruitment threshold. As the force required - in this case to turn the pedals, increases, larger type 2 fibers are recruited to assist. These fibers have a higher recruitment threshold, twitch faster and hence can produce greater amounts of power. This comes at a cost however – as stated above, these fibers will fatigue quickly.

You can’t change the makeup of your body’s locomotor muscles. Your genes dictate the percentage of type 1 to type 2 fibers. Something you are born with, and that in principle can’t train your way out of. Whatever you do in your training, a type 2 muscle fiber will remain a type 2 muscle fiber. It is true however, that a type 2 fiber can adapt to a training load and develop a limited capacity to utilize oxygen to produce power – so-called type 2X fibers can become type 2A fibers. Still, clearly those riders who are genetically made up of a greater percentage of type 1 fibers with their greater blood supply and higher mitochondrial density, will have the edge when it comes to sustained high intensity efforts at threshold or below. On that climb at BCCC I was recruiting less type 1 fibers and more fatigue-prone type 2 fibers than my competitors. Yes, perhaps they had made more advanced adaptations to their cardiovascular systems, but working well aerobically calls for efficiency in the entire energy production system. More type 1 fibers equals more aerobic capacity.

Tadej Pogačar. Skinny ectomorph only good at Climbing? Hardly. Pog can put down more power at the end of a race than most in the pro peloton

Training to Overcome

Is it a done deal then? Are we all destined to be one-trick ponies and should we therefore never expect a good result unless the course profile exactly matches the kind of efforts we are naturally built for? At the sport’s elite level that may be true. Mark Cavendish will never be first up the Alpe d’Huez, and Jonas Vingegaard will never outsprint Jasper Philipsen. Much of course comes down to racing smart and getting yourself in the right moves, but at the amateur level at least there are ways to level the playing field somewhat through the right training.

If you are of the mesomorph type – bigger and more muscular, spending time working at zone 2 intensities will help develop your aerobic energy system including making the type 1 fibers you do have more efficient. Training at this level leads to increased vascularization of the involved muscles as well as more mitochondria – the organelles within the muscle cell that use oxygen and glucose to produce power. You can work harder and still achieve these gains of course – the body is still using oxygen to make power right up to VO2max, however beyond zone 2 you’ll be generating considerable stress on your body and most likely recruiting more easily fatigued type 1 fibers. You’ll carry that fatigue into the following days, limiting the overall time you’ll end up spending working the target energy system. There are many well-documented benefits to zone 2 training, with increased efficiency of your slow-twitch muscle fibers high on the list.

If you are an ectomorph you are probably doing just fine as far as type 1 muscle fiber count goes. Since you’re probably spending a lot of time doing what you do best – sustained climbs, you may only rarely reach the level of intensity needed to fire off those high recruitment threshold type 1 fibers. Although you’ll never have the same quantity of these fibers as your mesomorph peers, you need to train what you do have in order to increase your competitiveness when it comes to all-out power. You may not ever want to contest a full bunch sprint, but if you arrive at the line with a small group after a day of climbing, some well-developed type 2 fibers will make all the difference. Get to the gym where heavy resistance reps activate ALL of your muscle fibers including those with a high activation threshold. High power /short duration intervals will also work, as well as higher rep sets on the leg press /squat rack. However maximum force production depends on recruiting muscle motor units with the very highest thresholds. Go heavy. Once a motor unit is recruited, less activation is needed to reactivate it, so over time you are teaching these fibers to become more responsive to your power needs.

You’ve Got This!

Just finishing a stage race like Baker City is a massive accomplishment for any amateur cyclist. Something to be embraced at all ability levels and no matter what your relative strengths and weaknesses are. With the right training approach you too can end up at the pointy end of the pack, whether it’s a flat sprint stage or a big climb. Working with a coach and following a structured plan based on your specific goals is by far the best way to get the most out of the time you have for training. At Dialed Performance Coaching we make sure to tailor every workout so you are ready to be competitive whatever your goal events are. Contact us at www.dialedperformancecoaching.com for more information.

Zone 2 and Your Winter Training Routine

Zone 2 training is all the buzz these days. In the racing off-season especially, we are told that zone 2 rides are where we should be investing most of our time on the bike, but why is that? When the days are short and the weather is crappy, it’s definitely tempting to question your life choices and we often find ourselves wondering “why am I doing this?” – what purpose is this serving? My advice has always been to ride with purpose – cut out the junk miles and make every ride count for something – so what are we actually achieving on those long winter Z2 rides, and how is it any different to the old-school ‘long steady distance’ rides that have always been part of the ‘tradition’ of off-season bike training?

Zone 2 training is all the buzz these days. In the racing off-season especially, we are told that zone 2 rides are where we should be investing most of our time on the bike, but why is that? When the days are short and the weather is crappy, it’s definitely tempting to question your life choices and we often find ourselves wondering “why am I doing this?” – what purpose is this serving? My advice has always been to ride with purpose – cut out the junk miles and make every ride count for something – so what are we actually achieving on those long winter Z2 rides, and how is it any different to the old-school ‘long steady distance’ rides that have always been part of the ‘tradition’ of off-season bike training?

Let’s answer that last question first by establishing what zone 2 intensity is. Most cyclists are familiar with Andy Coggan’s 7 zone model of power intensity based on a percentage of maximum aerobic power. Zone 2 is considered an endurance pace – something you can maintain for several hours relatively easily. Since the idea of all training is to stimulate the body to make fitness-improving adaptations, TRAINING at zone 2 means riding at the high end of this range with the goal of gradually being able to put down more power for a given perceived effort. Physiologically this is the point where the energy demands of your muscle cells cannot be met by aerobic metabolism alone. You can see this in the lab if you ever do a submaximal power test measuring your blood lactate levels. At your “aerobic threshold” blood lactate levels begin to rise, indicating that your glycolytic energy system has been recruited to help out with the effort. Outside of the lab, you know you are there when you can still hold a conversation, but talking starts to become labored and you honestly would prefer your riding partner to just shut up so you can concentrate on breathing. This level of intensity is the sweet spot. The idea of training at zone 2 is to push this sweet spot ‘up the line’ so that it is occurring at a higher power output.

Blood lactate levels vs. power output. Ideally LT1 will occur further to the right along the graph

Your skeletal muscles are made up of several fiber types, broadly classified as ‘slow twitch’ or ‘fast twitch’ (type 1 or type 2). The proportion of the fiber makeup is dependent on your own body type and the influence of your genes. Generally, successful endurance athletes will have a greater percentage of type 1 fibers, and athletes involved in shorter, explosive efforts such as sprinters, will have a relatively larger percentage of type 2 fibers. Training at zone2 intensities is targeting your aerobic system as a whole, but critically we are looking for adaptations to the type 1 muscle fibers so that they become more efficient at producing energy aerobically. Your muscles will increase in mitochondrial density as well as increase in vascularity, giving them more ability to process oxygen, . The increase in the number of mitochondria as well as their size, and the increase in blood flow to the working muscles ultimately means more efficient processing of oxygen and glucose to produce energy.

As an added bonus, the fuel used in the slow twitch fibers to produce energy is predominantly fat at these intensities, so by extending your body’s ability to utilize fat as fuel, you’ll be able to work longer before eating into your limited carbohydrate stores. Carbohydrates can be replenished during the race or workout, but only at a certain rate. By fostering the ability to run longer on fat, you’ll be able to hold on to your carb reserves for when they’re really needed – during those intense efforts such as bridging to a breakaway, or powering over that final steep climb.

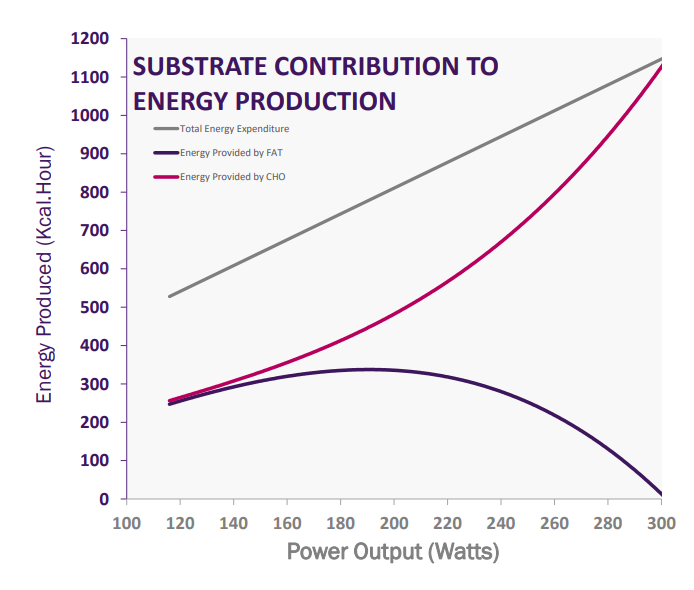

At lower intensities fat is a predominant source of energy, however carbohydrate is used exclusively to fuel high power efforts. Training at Z2 helps the muscles rely on fat metabolism at increasing intensities

In short then, ride Z2 during the winter months. Focus on steady smooth, long efforts, but ride with focus and purpose. These are not just long slow steady rides, but rather specific, and effective, work for your aerobic base. Unlike intervals done at higher intensities, the gains made through Z2 training can be long lasting - carrying you through to the intensive and event specific work you’ll be doing as race season gets closer.

If you’re interested in getting personalized advice to optimize your winter training, consider contacting us at Dialed Performance Coaching. We offer personalized, structured training programs that fit in with YOUR schedule and are based around YOUR goals. At just $175 per month, it is for sure the most effective way to get into the shape of your life and take your cycling to the next level..

Why the Best Use of Your Off Season May be to Take out a Gym Membership

By now most competitive cyclists are aware that augmenting your on-the-bike training with some gym work can significantly help you reach your performance goals, but why exactly is that? In this article we’ll discuss the direct benefits of a strength-building program, and in particular why you should incorporate it into your off-season routine.

By now most competitive cyclists are aware that augmenting your on-the-bike training with some gym work can significantly help you reach your performance goals, but why exactly is that? In this article we’ll discuss the direct benefits of a strength-building program, and in particular why you should incorporate it into your off-season routine.

Many endurance athletes have been reluctant to take out a gym membership, either because they think that the whole gym scene is just not for them, or commonly because they think that adding muscle in the gym will increase their overall weight and hence slow them down on the bike particularly when climbing. As a consequence a lot of athletes either avoid the gym completely, or they may dabble in resistance training, but falsely believe that a high rep /low resistance approach will net them the best results and avoid ‘bulking up’ with unwanted muscle mass.

Let’s address this concern from the get-go: while an increase in muscle size – ‘hypertrophy’, will to some degree eventually manifest from a sustained resistance training program, this does not always equate to a bad thing. Indeed an increase in lean muscle mass will generally increase your resting metabolism – more calories are needed by your body in its resting state. Your weight loss or weight maintenance goals are more easily achieved with a greater percentage of lean muscle mass. If you do put on a couple of pounds in new muscle, this is largely offset by your body’s new-found ability to burn through calories at a higher rate. Secondly, studies have shown that hypertrophy will occur only after several weeks of training and that during the first eight weeks or so of a resistance training program, adaptations will take the form of efficiencies to the neural system which we’ll discuss below. Finally the science has shown that athletes who genetically possess a relatively large proportion of fast twitch muscle fibers may have a greater potential for increasing muscle mass than individuals possessing predominantly slow-twitch fibers. This means of course that if you are a lightweight climber type of cyclist, the chances of you putting on a significant amount of extra muscle mass is small however much you can lift in the gym.

On the subject of using lighter weights through more repetitions, this is not the ideal way to realize the benefits associated with a strength building program. If you do a whole lot of squats or deadlifts with a light weight, you are essentially just replicating what you would be doing out on the bike. In order to realize all the benefits from weight training, you must lift heavy. In gym-speak this is often expressed as a percentage of the most weight you could perform a given movement with for one repetition – your ‘one rep max’ (1RM). Your lifts should be at a high percentage of your 1RM – enough so you can just make it through 8-10 reps with the last rep of each set at close to failure.

After discussing a couple of the common myths around strength training for endurance athletes, let’s look at why you should be hitting the gym and exactly how anaerobic training and resistance training in particular, will make you a better athlete.

You want a better sprint

If you race a lot of crits, race on flatter courses, and consider yourself a sprinter, then this goes without saying. Bigger muscles with efficient, well trained firing mechanisms generate more force faster, and more force through the pedals means more watts. If you find yourself in a less-than-ideal position when it comes to the dash to the line, the extra horsepower can make all the difference.

This advantage is often overlooked by people who consider themselves non-sprinters. We all know that so often, in amateur racing at least, a solo breakaway can have a big chance of success if the course is undulating and you’ve got the aerobic fitness to pull it off. So often the guys behind you just can’t get organized enough to chase you down. However, more often you’ll find yourself out there in a reduced bunch of like-minded and determined breakaway companions. Short of the classic last KM flyer, it is all going to come down to who can put down the most watts in the last 200M. At this point you will be thankful for all the squats, leg presses, and deadlifts you were doing in the off season.

You need to race harder, longer.

Resistance to fatigue is no doubt a marker of fitness and one of the goals we all set ourselves when doing any kind of training. Whether doing vo2 intervals, or steady-state Z2 rides, we can outride our competition by increasing the time it takes to reach exhaustion for any given effort intensity through dedicated training sessions. What a lot of athletes underestimate is the power of resistance training to increase our muscles’ time to exhaustion.

Anaerobic exercise including heavy weight training results in substantial reductions in muscle and blood pH values. With adaptations to consistent acute changes in blood acidity (i.e., increased hydrogen ion concentrations), buffering capacity can improve. This increased capacity allows you to better tolerate the accumulation of hydrogen ions within the working muscles, resulting in delayed fatigue and greater muscular endurance. Resistance training and other anaerobic efforts such as intervals performed above lactate threshold have been shown to significantly increase buffering capacity.

You want to avoid getting injured.

Bicycle racing is an inherently dangerous pastime. Sometimes it feels like it’s not a question of if you’re going to get injured, but when, and how long and painful will it be to get back to riding and racing. To compound the risk, sitting on a bicycle seat and turning the pedals around is obviously non-weightbearing, meaning that despite all the hours of training, the body has no real stimuli to adapt and strengthen the connective tissue and bones, leaving them vulnerable to breaking and stretching.

Weight training in the gym can result in both increased bone mineral density (BMD) and adaptations that increase our tendons’ ability to withstand greater tensile forces. Forces generated by increased muscle contractions subsequently increase the mechanical stress on our bones, and the bone itself must increase in mass and strength to provide an adequate supporting structure. Additionally, tendons, ligaments, and facia adapt to consistent anaerobic exercise that exceeds a certain threshold of strain. This strain threshold is seldom, if ever, reached during regular riding, including hard sprints.

Because bone and connective tissue respond favorably to mechanical forces, the principle of progressive overload – progressively placing greater than normal demands on the exercising muscles – applies when training to increase bone mass or connective tissue strength. While these adaptations don’t happen overnight, a good gym program should always incorporate progressive overload, and if these workouts are something you can stick with for the long term, you will see gains beyond stronger muscles and higher endurance, and perhaps save yourself a long and painful trip to recovery after injury.

You want to maintain or lose weight.

Winter is the time when many of us start to pack on a few pounds. It is often assumed that the body’s natural response to the cold winter months is to add on some insulation and perhaps there is some truth to this especially for those of us who live in the far North or South of our respective hemispheres where the winter months are indeed cold. And dark. And often wet. The more likely culprit is that we’re just eating the same as we did through the summer, but with a far lower calorie-burning exercise load.

As mentioned previously, although muscle is pound-for-pound more dense than fat, the more of our body that is made up of lean mass (muscle), the more energy it takes to sustain that body – our metabolic rate will increase and we burn through more calories even at rest. Putting on some muscle mass is therefore not always a bad thing for the endurance athlete. Unless you accompany your weight training campaign with an associated increase in calorie consumption the net result of your efforts is likely to be a drop in body weight as well as a gain in strength. If that sounds like a recipe for success, you would be correct although that last point about over fueling for your gym workouts is certainly important – many people assume a high calorie demand for a gym session, and this is not always the case. Loading up with carbs as you might do before a two-hour ride is probably not something you need to do before hitting the gym for an average lifting workout unless you are going to throw in a bunch of cardio work at the same time, which in itself is not a good idea as we’ll explain below.

Top tips on becoming a gym rat

The gym is a very foreign and occasionally intimidating place to walk in to for many endurance athletes. There are plenty of resources online to get you started, but a great way to begin your new routine would be to get together for at least one session with a personal trainer. It may cost a few bucks, but you’ll save in the long term by not wasting your time doing stuff that is not getting you to your goals. This is very important – you need to get the techniques right, you need to get the volume of work right - amount of sets, amount of reps per set, and you need a program that specifically targets the muscles that you, as a cyclist, want to train. You need a program that incorporates progressive overload – sets that get harder incrementally each week. And just as in ‘regular’ bike training, you’ll need to know when to rest up. Just like doing intervals or endurance training, the real changes occur in the time between efforts.

It's also important not to totally swap out your on-the-bike training for your new-found love of weight lifting. Each work out type compliments the other. For example, if you do end up increasing your muscles’ cross sectional area (CSA) through hypertrophy, this will ultimately result in a muscle cells that are less dense in mitochondria and muscles with decreased capillary density. You can compensate for this by adding in weekly longer endurance rides at zone 2 where both mitochondrial and capillary density are stimulated to increase. Just don’t ride on the same day as your lifting days, or at most limit riding to a shorter Z1 /Z2 cruise AFTER your gym work. A high cardio load such as a long and/or hard ride will leave you with too much central fatigue to successfully complete your gym workout. At best you will compromise your training potential and at worst you could end up overtraining and needing time off from ANY workout.

An eight to ten week program of 3 to 4 sessions per week in the gym over the winter will pay dividends. During this time, adaptations to the heavy lifting regime will manifest in the form of improvements to the muscles’ neural systems – muscles will fire more efficiently, especially the otherwise little-used power fibers – the type 2x fibers that are rarely stimulated for use. When your muscles eventually start to lay down new fiber and grow in cross section, added strength and endurance will follow.

When the Spring comes around and you have the motivation and need to get back on the bike more often, don’t give up the gym completely. A maintenance session or two per week will ensure you hold on to all those gains throughout the year. Just maybe avoid the big legs day in the gym right before a race or your local weekend group drop ride.

If you’re looking for more personalized advice on incorporating a resistance training program into your winter routine, consider contacting us at Dialed Performance Coaching. We offer personalized, structured training programs that fit in with YOUR schedule and are based around YOUR goals. At just $175 per month, it is for sure the most effective way to get into the shape of your life and take your cycling to the next level..

Five Things You Should be Doing in This Off-Season

Five Things You Should be Doing in This Off-Season

Winter is upon us. The days are shorter and it’s getting less and less appealing to get outside on the bike. The indoor trainer awaits, but do you have the motivation to stay focused on your goals and maintain some level of fitness though the months ahead? Here are five suggestions to make your off-season more rewarding and productive.

Take Some Time Off the Bike

You know you’re going to hate it when Strava tells you that you’re falling behind pace, your profile page shows a big gap in an otherwise consistent accumulation of training miles, and you stop getting those kudos. Moreover, a lot of cyclists have set an annual target milage or weekly time on the bike goals, and it’s hard to let these things go. The community aspect of Strava is a real thing, and when we’re not out there smashing the miles and uploading our achievements, it’s easy to feel disconnected from our cycling brothers and sisters. Easy too to feel that our hard-earned fitness is leaking away if we’re not putting in some kind of milage. There is some truth to that. Some level of fitness will be lost if we just stop cycling, just like if you get sick or injured during the racing season, there will be some lost ground to make up. However, most of these lost gains will come from your high-end power, and unlike getting side-lined during the racing season, this shouldn’t matter so much during the off-season. Your high-end power is the quickest to respond to a training stimulus once you get going again.

I advocate for taking a break from your cycling routine. With the racing season a long way off, and motivation waning, your rides are probably becoming more and more unproductive anyway. Sure you could reach that yearly target milage goal if you just keep going, but at what cost? Burning yourself out now might mean a sluggish start and lost opportunity when next year’s campaign really needs to kick off. It doesn’t have to be a long break. Perhaps 2-3 weeks of just doing something else. That’s enough to reset and recharge your motivation and hit the new training season with added enthusiasm.

Get to the Gym

Numerous studies have shown the benefits of weight training for competitive cyclists. Repetitive stimulation with heavy resistance exercise and a program that applies progressive overload to the target muscles over time will lead to hypertrophy – your muscles will become bigger and stronger. More importantly though, weight training can act to stimulate the nervous system to recruit more muscle fibers into action for any given load. This way our muscles become more efficient at the work we do. You don’t have to be a sprinter to realize the benefits of training in the gym – more muscle recruitment means more power at any level of effort.

While hitting the gym 3-4 times per week during the race season is obviously a recipe for soreness, fatigue, and poor on the bike performance during races and hard training efforts, concentrating on resistance training during the off season makes much more sense. Work with heavy weights – high repetitions of light loads essentially just replicates what you do when you’re out there pedaling. Squats, deadlifts, lunges, and other movements that work your quads /glutes and core muscles at a weight you can manage for 8-10 reps will best provide the stimulus. In addition, if you’re trying to lean out before next season and are on a weight-loss diet, adding in resistance training will help ensure you don’t lose too much muscle mass along with the fat you’re trying to drop.

Lose Some Weight

Power to weight ratio is perhaps the single most important metric when measuring your potential to be competitive on the bike. With many of us over-indulging during the winter months there’s often a panicked push to drop a few kilos as we emerge into Spring and the first race or the first competitive group ride is right around the corner. The body’s natural tendency to add insulation during the winter months, together with all the temptations of the holiday season almost always result in added weight during the winter months.

In many ways this is an ideal time to knuckle down into a weight-loss diet. Of course as endurance athletes we should be concerned about a healthy, nutritious diet at all times during the year. We need quality fuel to do what we do and we need quality nutrients to rebuild and maintain our bodies during periods of heavy activity. During the winter months however, for some athletes I would argue that it’s a good time to try to maintain a calorie deficit. This is the time of year that you are otherwise most vulnerable for weight gain and also the time of year where workouts can stay at a lower intensity where you don’t need to constantly worry that you’re not getting enough carbs to fuel your rides.

You should aim for a daily deficit of around 500 Kcals per day. Since each pound of body fat is equivalent to 3500 Kcals, this should result in a weight loss of about a pound a week – a healthy and sustainable target. Calorie deficit eating should be a temporary thing for endurance athletes, and you’ll need to get back to maintenance consumption when you’re ready to start high intensity training or racing again. Of course it goes without saying if you are one of the many athletes that have ever struggled with an eating disorder or body dysmorphia, you need to be very cautious in your approach to weight management.

Calculate your resting metabolic rate (RMR) and add on your best estimate for the energy you burn on a typical day just going about your life. Try to make this as accurate as possible. I like to use an app then to then track my calorie intake and keep to my target deficit. 10 weeks of this and you will have escaped the usual winter weight gain and enter the racing season with a competitive edge.

Ride at Zone 2

Traditionally the winter off season is a time for long endurance miles to build a good ‘base’. While it is true that concentrating on the lower end aerobic fitness this far out from racing is a good strategy, so many athletes spend hours suffering on long rides in crappy conditions and see little in the way of measurable gains. Especially when the conditions outside are grim, it’s important not to ‘waste’ your time and energy by just adding more junk miles. Make each ride count for something and you won’t feel like you are just suffering through the miles. Equally, don’t burn yourself out with hours of indoor training without purpose.

Zone 2 is not an easy spin. It’s not a recovery ride. The perceived effort should be at the top end of your ‘endurance’ zone. You should be able to hold a conversation at this effort, but it will be strained. While it’s true that these rides should ideally be longer than a quick hour after work, even shorter rides at the correct intensity can bring you gains. Working at Zone 2 brings positive adaptations including increased amounts of mitochondria in the muscle cells, as well as increases vascularization bringing more blood into the muscle fibers. Perhaps equally important though, working in this zone helps to push out the point at which the body relies more heavily on carbohydrates to fuel the effort. If you are able to ride longer and harder while still burning through fat as a fuel source, you’ll have the advantage of not having to consume high amounts of carbs during an event, saving your carbohydrate stores for when they’re really needed – bridging to a break, staying with a big surge, or sprinting for the line.

Make Some Plans

In the winter months generally the next year’s racing calendar is still taking shape, but some high-profile events are already scheduled and already selling out fast. This is a great time to assess what your goals will be for next year, and secure entry to your target events before they’re sold out. Next, get them in your training calendar so you can work up a plan to be at the top of your game for the most important stuff. Having definitive goals to work toward will help you stay motivated and focused on what you need to do to have a successful season when it finally comes around.

Working with a coach can take the guess work out of your off-season training. Perhaps more than at other times of the year, being held accountable can make all the difference between spending the winter months losing your fitness and motivation and accomplishing a rewarding, productive training block and being in the best shape possible for next season’s challenges.

Unlock Your Full Potential: How a Cycling Coach Can Improve Your Performance

Unlock Your Full Potential: How a Cycling Coach Can Improve Your Performance

Introduction

Cycling is a thrilling and challenging sport that offers numerous physical and mental benefits. Whether you're a beginner looking to build endurance or a seasoned rider aiming to take your performance to the next level, a cycling coach can be the secret weapon to achieving your goals. In this post, we'll explore why hiring a cycling coach can make a significant difference in your cycling journey and help you reach your full potential.

Personalized Training Plans

One of the most significant advantages of working with a cycling coach is the creation of personalized training plans. Unlike generic online training programs, a coach will tailor your workouts to your specific goals, fitness level, and schedule. This individualized approach ensures that every pedal stroke you take has purpose and each workout is designed to improve your performance.

Expert Guidance

Cycling coaches are experts in the field. They possess a deep understanding of training principles, physiology, and biomechanics. With their knowledge, they can help you optimize your training regimen, fine-tune your technique, and make informed decisions about nutrition and recovery. This expertise is invaluable for avoiding injuries and maximizing your performance gains.

Accountability

One of the challenges many cyclists face when training alone is staying motivated and accountable. A coach provides the necessary structure and accountability to keep you on track. Knowing that someone is monitoring your progress and providing feedback can be a powerful motivator to consistently push your limits.

Objective Feedback

Cycling coaches offer an unbiased perspective on your performance. They can identify weaknesses, correct form errors, and offer constructive feedback on areas that need improvement. Having an objective viewpoint can be crucial for addressing issues that you might not notice on your own.

Mental Toughness

Cycling is not just a physical sport; it's also a mental one. A coach can help you develop mental toughness, resilience, and focus. They can teach you strategies to overcome self-doubt, handle adversity during races, and maintain a positive mindset, which is essential for consistent performance improvement.

Race Strategy

If you're a competitive cyclist, a coach can provide race-specific guidance. They can help you devise a race strategy, understand your competitors, and make tactical decisions during events. With their expertise, you'll be better prepared to perform your best when it matters most.

Injury Prevention

Cycling can be physically demanding, and injuries are not uncommon. A cycling coach can help you prevent injuries by ensuring that your training loads are appropriate and by teaching you proper techniques to reduce the risk of overuse injuries. They can also guide your recovery process if you do encounter an injury.

Long-Term Progress

Consistency is key to long-term progress in cycling. A coach can help you set realistic long-term goals and create a sustainable training plan that avoids burnout. They'll ensure that you progress gradually, allowing your body to adapt and improve steadily over time.

Conclusion

While cycling is a fantastic sport for fitness and enjoyment, achieving your full potential as a cyclist often requires professional guidance. A cycling coach can provide you with personalized training plans, expert advice, accountability, and mental support that can elevate your performance to new heights. Whether you're a recreational rider or a competitive cyclist, investing in a coach is an investment in your cycling journey's success. So, why wait? Partner with a cycling coach today and pedal your way to peak performance!